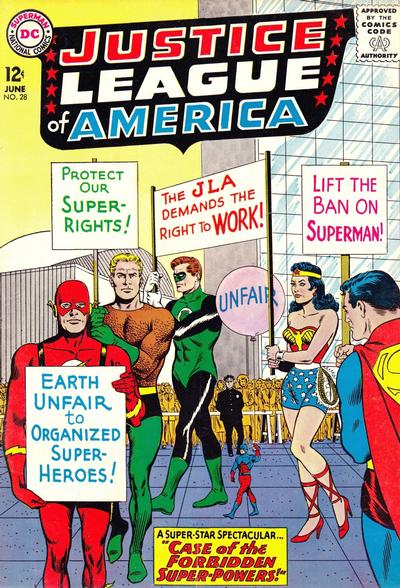

I spent four hours this morning at the entrances to Lancaster University, picketing for my union, UCU, who are involved in an ongoing industrial dispute centred around fair pay. I was joined by colleagues from across the University: members of UCU and the other main campus unions (UNITE and UNISON) but also by students from the Lancaster University Anti-Capitalist group, who brought radical slogans and music.

Spirits are usually high at the picket line – we feel like we are doing something to bring about positive change, we are standing up for our rights and supporting each other. And today was no different: many people stopped at the picket line while driving, riding or walking past, took a leaflet and perhaps exchanged a few words with us. But others drove straight past, stern-faced and with windows (and minds) firmly closed.

There is almost never enough time to fully explain why we’re striking, which is one reason we have our leaflets. But more than once today I wished I had been able to say my piece, to express my thoughts in full to some of the people passing. I’m not talking about the strike in general, which is more than adequately explained on the UCU website (see http://fairpay.web.ucu.org.uk). I’m talking about some specific things I would have liked to say to some of the individuals who passed me.

To the student who, when I said we were striking for fair pay, answered “well I pay £9000 and I’m not getting my lectures”:

You’re right. You pay a lot for your education. I protested against the introduction of tuition fees, as did my union. I am deeply opposed to the ideologically loaded fees policy, which reduces opportunities for the least advantaged, increases inequality, and will cost much more in the long run than not charging any fees at all. But given that you will pay these fees (one day, once you earn enough), where would you like to see the money invested? In prestige projects that make the campus look pretty, but are often designed by architects who have no idea about what university teaching actually involves? In Vice-Chancellors’ salary increases (more than 5% up on average just in the past year)? Into maintaining what is arguably an excessive surplus (currently £1bn or more in the sector)? Or in the dedicated, highly qualified staff who make your education possible, and who determine its quality? I think the students who stood side-by-side with us today expressed it better than I can: “Support the staff who support you”.

To the many colleagues who passed by who are not members of a union:

I’m here for you too, not just my fellow union members. But are you happy to accept any gains we might win? Or will you turn down a salary increase that might arise from our industrial action? Do you enjoy the rights and benefits that have been brought about or enhanced through past industrial action, such as weekends, regulated working hours, holidays, pensions, appeals processes, anti-harassment and anti-discrimination rules, workplace safety rules, rights of redress… I could go on. All I can ask is that you consider joining (or re-joining) the union – for teaching or research staff (including postgraduates who teach) this can easily be done here: https://join.ucu.org.uk.

To the colleagues who are members of a union, but still crossed the picket line:

You are harming our cause. The point of industrial action is that all members of the union act together, with the only tool that we can (lawfully) use to compel our employers to listen to us: withdrawal of labour. If you come into work, work from home, or rearrange classes for another day, you may as well wear a big sign saying “feel free to walk all over me”. You may disagree with this particular action, or think that you earn enough already and so have no need to take part. But unless the union supports its weakest members, including those who are not as fortunate as you, it is not a union. The union is a representative democracy, and like many such institutions, it can never be perfect for everyone. And when you are more personally affected, how would you feel if your colleagues turned their backs on you? If you are targeted unfairly as an individual, will you ask the union for casework support? Finally, even if you are not concerned about pay, this should not stop you from taking part in the action: I’m not striking because I want more money, I’m striking because I am disgusted with the inequality in the sector, with VCs often earning more than 20 times what the lowest paid earn, and because I am deeply concerned by the ongoing marketisation and commercialisation of education.

To the lorry driver who cancelled his delivery to the university and turned around because he did not want to cross our picket line:

Thank you. The world needs more people like you.